Interview with Peter Graf

Credits

- Cristian Aquino, Lead Researcher

- Jan Virsunen, Interviewer Coordinator

- Chienyu Chen, Post Production

- Thomas Nazaradeh, Editor

- Your Name, Web Manager

- Web Design: Sarai Mateo, Cristy Aguilar, Anna Huynh, Rosa Salangsang, Richer Fang, Vanessa Rivera, EJ Gandia, Cameron Chung

Abstract

This article, Interview: Joel Slayton is just that, an interview with CADRE Founder Joel Slayton.

Bio

Peter Graff is a developer based in Munich, Germany. He is the Co-founder and Director of Engineering of the Web 3D compnay, blaxxun interactive AG. He was the leader of product development for the Community Server product.

Article Body

Rhonda Holberton 00:00

Okay, so please introduce yourself. So for example, my name is Rhonda Holberton. And I'm the new media artist based in San Jose, California.

Peter Graf 00:08

So my name is Peter Groff. I'm a software developer. And I'm based in Munich, Germany. I've also lived in the States for five years between 94 and 99.

Rhonda Holberton 00:19

Wonderful. So we're going to start way back before we kind of work our way up to verbal in the 90. So what is your earliest memory? Do you have developing technology?

Peter Graf 00:30

My earliest memory of developing technology is that I started university in 1981, in Germany, in Munich at a table machine. And there, I think, in 1983, or so I got into a group of people, we had a Microbox that was running a version of Unix. And I started to do network based TCP IP programming on Unix. And that was basically, I think, the first real development activity that I had. From there, the group leaders were all PhD students, and after they finished their PhD, they went on to a company in Munich called Softlab. When I finished university, I also joined in there, and we were doing the same type of Unix based network programming. Basically, this was more LAN based network programming. The Internet didn't really exist in it as it existed, of course, but nobody was doing as at least not in Germany, not anybody was doing anything over it. But there were in-house [networks], corporate networks existed. And so we did Unix based in-house. For example, one thing I did was a big warehouse for BMW, basically keeping track of what is where and those robots as it was all done by as it was fully automatic. And so basically keeping track where everything was labeled with barcodes and barcode readers and stuff like that. So when the internet came along in 1993-94 I had already programmed in C++ for TCP/IP connection, and Unix programming for almost 10 years. The internet felt very natural.

Rhonda Holberton 02:15

Great. So maybe as a follow up question to that, how did you find your way to Web 3D, or what's being commonly referred to as the metaverse these days?

Peter Graf 02:25

First, I found my way to San Francisco. I got married to Tamiko [Theil] in 91. And in 94, we decided to move to San Francisco. So in September of 94, we arrived in San Francisco. And at that time, friends of Tamiko’s, who had been working for Thinking Machines in Boston, a whole group of them had moved to San Francisco. And they were doing a company called WAIS (Wide Area Information Server) Incorporated, Brewster Kahle was doing WAIS Incorporated, which was at that time an internet search engine technology, and I worked for them for half a year; from September of October of 94 till April of 95. And at that time, the net really took off and everybody was talking about the Netscape browser and Netscape went public, and whatever it was, all these things were happening.

And at that point, some friends who had worked with me at Softlab in Munich got in touch with me and said, We have funding for a startup. And we want to start an internet company. And by the way, you have to read Snow Crash. That's what we're up to. Okay, I read Snow Crash, they called themselves, or one of them actually came over and said, Okay, I want to start a company called Black Sun, like in Snow Crash. I think the company that runs the Metaverse [in Snow Crash] is also called Black Sun, basically it’s a term that we took from Snow Crash. More or less our business plan was also taken from Snow Crash. So that was really at that point we started out. That was in July of 95. We started off with blaxxun interactive. First in Munich, but it was clear for us the investment money came from the US. So it was clear that we needed a presence in the US. So we started a US company and a European company. And I was basically the US company. The US company was run out of the back room in our house in the Mission [district in San Francisco]. And as a US company, I think for the first year or so, exactly as a PC under my desk that was running 24/7 and there was also my web server.

Rhonda Holberton 04:47

And just a little bit of context. Can you tell us what was its primary focus and what were some of the early projects or kinds of applications?

Peter Graf 04:54

You know, the primary focus of blaxxsun was really was the metaverse or cyberspace, there were different terms for it. So what we really started as a very first version, we were a sister company I invested also invested in Lycos. And Lycos at that time, like Yahoo, was a very big search engine, but it also had categories. So basically, you could also websites were rated and recategorized. What we did as a very first project was called Point Worlds. We took this the Lycos data that basically said, what are the top, let's say car manufacturer websites, what are the top educational websites? What are the top medical websites, and they had a rating that as they categorized the websites, they rated them. And we basically took those numbers from like cost rating numbers from like us, and transferred them into 3d characteristics of buildings, then create a village so to speak, with a circle of houses around then if you clicked on the house, you basically got to this website of the car manufacturer, or the educational or whatever the topic was. So this was the first thing. But for us, it was always cyberspace, we wanted to have exactly this thing. We wanted avatars in 3d space. In the actually talking to other people meeting other people. This was always our main focus.

Rhonda Holberton 06:17

As a follow up to that; at the time, there were text based Internet search engines, kind of that was a feature. And so you're kind of building on top of that, what is it about the kind of 3d experience that you were producing that felt important at that time.

Peter Graf 06:33

What was important for us with a 3d experience was that we always saw it as a place where people could come together, chat, exchange information, and do this in 3d in a way more natural than just doing it without any [3D] presence. I mean, you can have a message board. And basically people can interact over the message. But for us, it was also we wanted to have a presence, people should have social interactions, I think that our 3d technology was always tied in with access. So it was not a browser that was a standalone thing. It was a plugin for Netscape and Internet Explorer, and later on other browsers, but it could always be embedded in a web site.

So basically, you could have a website with all sorts of information in that [with our plugin] you had the chance to put a 3d chapter. Now, very often, if I go to sites or buy something that is also still a chat, where I can chat to some salespeople or support people, or just other customers. And so that was our idea. But we wanted to take that into the 3d, very much driven by Snow Crash. In the book everybody meets in cyberspace. And like big things happen in cyberspace; it isn't exactly our vision, but I think it's very much the same. Well, what [Mark] Zuckerberg also announced a couple of months back, it was really the same idea.

Rhonda Holberton 07:55

Your experience with early local networks was also very much tied to kind of spatialized and material objects, like in the BMW production factory. Do you think that experience changed the way that you thought about interaction over the web?

Peter Graf 08:13

My experience with Internet technology, one thing that was clear for me is that the web should be much more interactive than it was at that time. It was all set most people's experience at that time was static web pages and message boards, those were kind of the only things. Things like Facebook or WhatsApp, or all those things didn't exist. There was one service, we actually really collaborated with them, an Israeli company, and on their service you could basically exchange messages very much like WhatsApp within a chat. We basically built a bridge between their technology and our technology, so that users that came from their client could interact with people that came through our clients, in order to basically increase the volume/ number of people that were interested in our back end service.

Rhonda Holberton 09:15

So maybe then to kind of dig down into that a little bit. What were some of the technological innovations that were significant or needed to be in place for the work that you were doing?

Peter Graf 09:26

The one thing that needed to be in place, and that was not very much existing at that time? It was a big problem for us; it was two things actually. One was good graphics cards, so that you actually could create a 3d world and a 3d world with enough polygons to make it worthwhile. And the first graphic cards that allowed that at all were on Windows 95, coming out in 1995-96, or something like that. And before that, you couldn't do any 3D on a PC. You could do it on SGI machines, but those were expensive and nobody would have been able to do that at home. But once we got the Direct X Windows based graphic cards and also OpenGL based graphic cards that came out at that time for PCs, then that was the one thing that made it happen. The other thing was, of course, collectivity. 3D content is rather big, nowadays it’s ridiculously small, but back then a megabyte download was something that people had to wait four to five minutes. Therefore, a [3D] world had to be about a megabyte in size. Yeah, just the imagery was multiple megabytes, which made [the experience] better in the end, but it was always a big problem for us.

Rhonda Holberton 10:39

Alright, so your vision was kind of ahead of the existing architecture or the technology in place.

Peter Graf 10:44

The other thing that happened once we stopped in 2002, Second Life, became rather popular. By 2008 or so everybody had a Second Life page, the German government, good Institute, and whoever, as everybody thought they did a second last page. And then I think about 2010, Facebook became exactly that type of marketplace that we had envisioned, only without 3D. And Facebook now has existed for 12 years, and has been in this marketplace. But now Zuckerberg also sees the need to put it in 3d. I think this is what's happening.

Rhonda Holberton 11:19

My next question is kind of that; what were some of the technological or cultural changes that have been implemented or that are now in place that allow the metaverse to have become a household term, and for Mark Zuckerberg to be interested in [3D] as a feature.

Peter Graf 11:35

The things that are now in place, and that were not in place in the late 90s is really the connectivity, and also the availability of voice chat. So what we are currently doing, [talking via Zoom], was not possible in the 90s. It's like there was a company called Online, they were also in online business in San Francisco. And we did some experiments, they had a voice chat over there. The problem was that you could connect more than like eight people to the server, and then the server was maxed out. So it was really voice chatting. And mixing the different audio channels was a real big problem.

When I saw the video that Zuckerberg brought out, these avatars didn't have a body and were very fixed. And those photos looked very much like they had the same restrictions our avatars had in ‘97. Ours got much better after, the whole thing we could not do was voice chat. So it was all text chat. What we had was a text to voice component, where you could basically configure your own voice like clarity and a lot of parameters. You could sound like a robot, like a man, speaking fast, speaking slow, high pitch, low pitch, quite a lot of parameters. And then basically, it would read the text that you type to the other people. So you would show up in any world and type the word hello, and your avatar would really say hello. No one really had microphones, that was not, I don't think it was doable in 2002. A little later, I had the first Skype conversation, I think Skype must have come out around 2002 or so. I remember we were in San Diego for half a year in 2002. And there I had my first Skype conversations with people in Munich, they knew about it, I didn’t know about it then. I think it really started out as a European thing and then made its way to The States coming from Estonia or something.

Rhonda Holberton 13:09

And we jump into a future-oriented question: Is there a specific project that you worked on or technological achievement that you kind of jumped over the hurdle that you're most proud of?

Peter Graf 13:21

Yeah. So I think the thing that I'm most proud of is really CyberTown was started by some guys in LA, I think also around 95/96 and they were the first to use some interaction technology. At some point, we got some and we met them. And they said, yeah, our technology is not really good. And we don't know whether it's still good, people are working on it. And we said, so if you want to switch over, we would like to have you because they were quite an active community. There were a couple of thousand people in there and it was a lively thing. CyberTown was run by Black Sun from maybe 1998 to 2002. And then we actually gave it back to them, and then they ran it for another, I think it ran until 2010.

First of all, we had a whole infrastructure of places; you could have your own private place like a private house that had a 3d representation, but also had a 2d representation is very much like a Facebook page that you could create later on. When Facebook came out in 2010, I really looked at it and to me it was like; we did all of this before. The ‘like button’ we didn't have, but everything else; that you can share information with other people, that you could post it on your page, and so on and so forth, that was all there [in CyberTown].

Let me talk a little bit more about CyberTown. So CyberTown first of all had private places that you could make very much like Facebook, but also in 3D. Then we also had a whole economy there. You could create stuff, upload it, sell it, and then other people could buy it so people were buying or creating flowers or pets or whatever. You could also have pets that had actions they could talk because they were chatbots. There was a whole system of a community there. There was a mayor, there were elections, there were public meetings. So it was really was a town; it was a space. I was basically the technological lead for all the backend of that. I was not working so much on the 3d side, I was working on the backhand side on the interaction side as it was still like [what I was doing before] with TCP IP network programming with a database in the back. There's also the care for distributed things like also, I think, very much like what Facebook does, all the web pages that need to be cared for. So we did a lot of things before Facebook did, we had done them 10 years earlier. We did a lot of things that Zuckerberg now wants to do that we had done in 25 years earlier.

I really remember when this Zuckerberg’s video came out this summer, I called some people I still know that were co founders of Pixar, and we got together at some point and we all laughed at this video. Mark Zuckerberg’s video was really so much what we had done 25 years ago, or 20 years ago. We really laughed at it but it was also like damn it, we should have, why didn't ours fly? I mean, I had this a couple of times; I had it with Second Life. But there I understood it. I know they were nice people, I think in the whole life of blaxxun, we spent about $30 million, mostly on development and of course on advertising. And I think they spent $50 million on advertising. So that made Second Life very big; Second Life was a household name. And we never got there. So [I understood] there was a reason for that. Facebook of course has its own story, but I don't know why they became so big.

Rhonda Holberton 16:31

Timing is everything, right? So this is actually kind of interesting. The fact that Mark Zuckerberg's future looks a lot like your past is the consideration of the next question. So at the time, when you were developing blaxxun, or all of these other kinds of other projects, what did you think that the future of web 3D was going to look like in 2022?

Peter Graf 16:48

What did I think the future of web 3d would look like in 2022? I said it, we never had to fill in and think about something 20 years in the future, but looking back now it's interesting. For example, the blalxxun technology still works on Windows 11 computers. There’s still users, Tamiko still uses it and built some of her artworks on the VRML browser that we had and this browser still exists, and it still works. And so you can use it out of the box on a Windows 11 machine, you can run it, which is very interesting. So they haven't really changed that much as Microsoft kept DirectX very stable from Windows 98. Up until now. So as I'm looking backwards from now, after feeling not much has changed, of course, iPhones, I mean, iPhones are the big thing that we did not see and having phones having iPads. This is a very big thing. We didn't see that now, would you dare to say something about 2040? What your computer would look like in 2040 to live as I went to work to live with a computer would look like? I wouldn't, because I have the feeling that I have no idea what I have no plan on what's going on. Of course, we all did voice chat, that was something we wanted, of course, also in Snow Crash there were these glasses so very much like the Oculus, and those cloth classes, those things, of course, we've thought about and we dreamt about it, but the ones that were existing then were like ones that were being experimented with at universities were these monstrous things, basically a laptop PC or some contraction in front of your face.

Rhonda Holberton 18:15

So you said you were starting to talk about something that I find actually incredibly interesting and might be particularly relevant to some of our students. So we started out this conversation, you were approached by a couple of folks who wanted you to come work with them as a developer, but they wanted you to read Snow Crash, right? And you even just said that as a developer you were just thinking about where you are now, like, what is your deliverable? How do you reach the goal? So when you think as a developer it’s very different from the way that you would think as an author writing speculative fiction about, you know, some imagined future or as an artist, right? And so it seems that Snow Crash was important to you. So how do you reconcile that long term vision through a creative process and the technological development within that framework, as you were kind of being asked to do at the time.

Peter Graf 19:03

The vision of something like Snow Crash and the technology, those people that approached me were all former colleagues of mine. So they were also programmers, and they had worked at the same team. And all six of us came from the same team, so they had just by some means, gotten a connection with an investor who had made a lot of money selling BookLink, a browser to AOL, and he wanted to reinvest some of that money. And so he gave us a couple of million, he basically started lots of different internet things. One of our founders, the co-founder, was a gamer. He was a developer, but he was also a gamer. And he played a lot of those Dungeons and Dragons, like fantasy games, and I think he was very much interested in this gaming. I think what he wanted to create was something like Witcher 3, but with other people. So that was this idea; together play in Witcher 3 in a group. I think he was the one who had read Snow Crash. And so he said, Hey, guys, read Snow Crash; this is a very interesting idea; I think that is really as this is all doable on the internet. So I read it, or we read it. And we said, hey, well, yeah, so from a networking point of view, as I said, from a networking point of view, guys, no problem, I can, in half a year, I can create the infrastructure to do this. And that's actually what I did.

On the front end, we also had people that came more from a gaming direction that knew how to do 3d programming. I think our first one, which was not VRML based yet, was kind of really poor. I think we all had too much of a business background, not a 3D artist background. And Then Holger Grahn, who was a developer from Berlin, in his spare time he had created a VRML browser. And he approached us at some point and said, I have a VRML browser, but nobody's interested, but I see that you might be interested. And we said, Yeah, come on board and you get the same amount of shares that we have and we’ll take your browser.

For us it was looking at Snow Crash, in reading the book, I clearly saw how to implement it. So how to implement this Metaverse; this Black Sun. I wouldn't have thought about it [otherwise]. Because actually, at that point, I didn’t spend a lot of my free time with computers. Not a lot of people did in 1994-95, there was nothing, I mean you could go to AOL. So therefore, I had a computer, I worked with computers, but I spent my spare time in North Beach in some Italian bars and not my computer. And then, of course, seeing the Snow Crash thing, then I understood Wow, this could be something like entertainment on the web. For me, the web was more of an information sheet. And that's also still how I use the web. I read The New York Times, I read Der Spiegel, I watch videos, I watch soccer, currently I'm watching soccer on the web. So I wouldn't check groups or anything, that never happened for me.

With [games like] Witcher [I felt] there was something there that Ilost. At some point I said, I need to see what those games can do. Some friends of ours have a daughter and she studies computer science and she became a studio intern with Tamiko. She stayed with us last January. And then at some point I said, so what games are you playing? She said, I'm playing Witcher. And I said, Can you show this to me? And said, Yeah, of course. So she installed it on my machine. As she played it. I watched her playing it for an hour or so. And then I read a couple of the books because I wanted to understand the backstory. And so yeah, that was it. I said, Okay, after I've seen the stuff and understand what it can do and how far they got with the realism that they put into those fantasy scenes.

We had always tried to get more realism into our 3d worlds. Like, for example, we had really beautiful avatars that we made in a cooperation with Canal+ Multimedia in France. They had a really, really beautiful world called Le Deuxieme monde, second world, where they recreated about 14 Different parts of Paris in VRML. Unfortunately, I don't have any of that. I don't know whether any of this exists. For example, I had a really, really beautiful plus the wash that in Amman is just a square, square shaped square with really nice buildings around it, or they had like a pyramid and move around. They had really beautiful worlds. And they also had an incredible avatar called what's called Avatar builder. You could basically start with a naked model in the first versions, even though it is for the American was we had to take them. And then you could basically put on underwear, you could put on clothes you could like you could resize all body parts and like longer arms, thicker arms, bigger head, smaller head. So on one hand, you could create very photorealistic avatars. On the other hand, you could also create all sorts of alien whatever figures in those avatars, they had all sorts of movements and stuff, you could really walk them around, they could jump, they could just move their arms. The only thing they didn't really do, they couldn't move their face. This is where you could have a facial expression on it, but that stays the same. That's perfect.

Rhonda Holberton 24:58

We're kind of discussing A the ways that kind of creative processes zipper up with more technological processes, you know, in the development of especially I think, kind of web 3d, but probably any new venture, you have to imagine it. And then what are the ways that a project without the technical back end are going to is going to fail? Like, if that's that in place, but also a project can fail? If it's, it doesn't have the vision, right, that kind of artistic or social work? There's lots of different ways. And I think you're you're starting to express some things like a couple of different threads, right? Like one way to approach I think hooking users is made it a more lifelike environment, or you're even talking about the young woman staying with you is into this world, both because I think it's a playable game that she likes, but there's also these like books and backstory. So there's this world building aspect that doesn't necessarily rely realistic polygonal modeling, but the reality is that we've created our head and then like, the other part of this, right, is that these things only work if there's users, right, like the kind of connective tissue, it has something that maybe you don't use the internet for that kind of social space. But I also think is an interesting thing to think about. Yeah, that's a really beautiful answer. I was like, I did like you. Perfect. Everything you were saying? I just like, Ah, wonderful. So we're kind of done with our formalized interview right now. But like, I think two follow up questions. That would be like, what happened? I asked you, yesterday should be asking, and then what should I be asking? You know, I'm going to be talking to me later today, you know, what should I be asking him? So those those two to kind of follow up questions?

Peter Graf 26:43

What should you be asking me what you have a little side story. And you might have noticed that like someone just started as out as black some as as color and star and ended as black. So with two x's in there, the story was that Scott McNealy, the head of Sun Microsystems at the point came to us and said he will not allow any software company with a result in it exists. And we told our investor who was at that time as a day Furthermore, this his name, he was like on the like the world's most richest person, he was just after Scott McNealy, like, somewhere in the 30s or something. And he said, No, we don't, we will not will No, no, we don't change the name. No, it's okay. It's okay. And Scott basically called and said, He will terminate all server business with like, and done before there was an oops, this is serious. So guys, you have to rename and then we like son with the two x's for one. And Scott, big lady was okayed. And then on the other hand, for us, it sounded the same set of speakers that that was the story there. Now even one of topicals friends from thinking machines are technically people from thinking machines actually ended up at some because when Thinking Machines went under 89 or 90 or so then some bought the technical side of it. And so they were really working with the working at Sun and one of them in particular, was really working closely with with Scott the meeting. And at some point, I talked to him and said, Could you like find out what, how serious this is? And within a day, he called me back and said period is really serious. He needs it. There's no way he's got it. He's not gonna go for it. So he's really he is serious about this. He does not want a company calls that has the word sun in it to exist. Okay. Then after he called whether on Saturday, he wants to terminate all server licenses with like us for like us. That was clear. He made businesses Yeah, so this was like, an inside story there. Mitra I met meet right ways. Actually, he was also I don't know how he came to these people said race. And then he went on to work for Worlds Inc, or chemicals also working. And from race, we traveled to Worlds Inc, and I went to Black Swan. And we have been friends since the waist. Now I think worlds has its own story. And you have to talk about it. One thing that I found out not too long ago, because Mitchell published it on the web, we had at that point, we had to work together on trying to create a extension to Vermont, that would be a vet protocol. So that you could basically interact with different virtual worlds on or interact between, like with an avatar from flex angled for Worlds world and vice versa and have objects from one world to the other. So we incorporated a lot of things and we had like, very tight meetings and cooperations. And at the same time, worlds was taking out patents on the whole thing which they got and then which didn't mean anything because like some went under no rules. in tandem, but like sudden become so had become successful, I think worlds would really have become a very nasty a very I haven't really talked to this about it. I haven't really talked too much about it. He was here like two months ago. But it didn't. It didn't occur to me to ask him but he published his paper, he was on the payment as well. And it was a couple of payments dedicated, they took out right at the same time. So basically creating a payment for all the stuff that we did together. And that was kind of a weird thing. And I said, Wow, this is interesting, interesting move, we really have to ask him at some point. Maybe this is not something that you should,

Rhonda Holberton 30:38

maybe it's not, but I think it provides me a certain amount of context to write to approach and it's, it's all well and good as long as you're scrappy upstarts. But as soon as there's real money coming in, and this might actually you know, that the patent that he does have, you know, if it was something that you operated together, I actually do think you know, as a Metaverse starts becoming more realized, and Zuckerberg in fashion, those might actually be something.

Peter Graf 31:07

I don't know whether this stays limited to like 10 years, or 15 years or something. Because if they were still active, they are all by worlds, I guess. So and I don't know where overall it's in a form as a residence like it existed for a long time. I know that like some of the old people still worked for it was still in existence as exciting one form or the other. Also students, it's like, when we shut down the company, we had sabotaged over to the guys in LA, and they ran it for like, 10 more years. But we also the Hogan, the guy who had brought a 3d browser to us, he also we handed it back to him. And he was two other guys from like sun started a company called manager. And that still exists that company. And they basically also ported the browser to the glasses. So that's how to cook and even now show her one of the world's with Oculus and device, she can show her run around her three pieces that she did there, she can show them in those classes, because bit management has ported the browser on to onto those other devices, basically, I mean, those classes are nothing but an Android device. And Android, in its core runs OpenGL. So if you have an OpenGL based Windows browser written in C++, you can basically compile it on Android and run it. So that is also the whole technology from back then. And that is really weird, still exists. And you can still run it.

Rhonda Holberton 32:40

Well, theater, I have a I've know that I've taken up more than of your time than we maybe had a lot it. But this has been so fun in such a treat. And I'm really excited about the next iteration of this where we can travel and we have travel funds, and they can fly out their crew.

Peter Graf 32:59

Oh, no, no, no, no, we do this, we do this in the metal. But yeah.

Peter Graf 33:07

That's that's something that I mean, I still have all the code. So I still have all that mix on code. And every now and then I go in and compile parts of bits of it. And most of compiles, because it's written in C, C++. And those languages also have not really changed a lot since the mid 90s. So sometimes people from cyber town, or the old people from as members of cyber town, they have a Facebook group, and they reach out and say, Ah, couldn't be like, restarted again. Couldn't be like compile it again. Can we run it again? And actually, I could be now. So if I hadn't started all this AR stuff, then maybe I would have sat down and said, Okay, let's see what I can do with that make sense? stuff. But no, it's yeah, it's other people can do that.

Rhonda Holberton 34:00

Yeah, I mean, you know, because I'm working partly with Tomiko. But other projects with museum collections, trying to figure out what is the technical solve for this, this problem? Is it keeping the code base updated? isn't really offering what does this look like? So that's something that with Tomiko, we're going to kind of be playing with some of the reauthorizing components. But my hope this project with real funding is that we can create a Digital Stewardship Center at San Jose State and work with developers on both kind of keeping code bases alive. But also,

Peter Graf 34:34

I have to make some code base but of course, I don't have to write to the exact code base. I don't actually know. Like, I know that at some point, the guy who was as we went into chapter 11, in 2002, and then basically, we shut down the company has actually shut it down and shut it down with like, almost like a zero loss. It was very, after the.com crash in 2001. It was clear that there was no market and as there was no stock exchange anymore to go to, and so that really entered it. And at the same time, we knew that we were cashflow negative, so to speak. And we knew that money would run out in six months. And so that's what we actually did, then after six months, we shut it down since February of 2002 shutdown. And I think there was actually very little x there was all more or less above water, but a very lost some investor came and bought everything for like 100 US dollars. So I don't know whether this investor still exists or remembers that he bought it. So whatever it is, I have to code but I don't have the rights to let's, so I was like thinking about just putting it up on GitHub, but even there, I'm kind of shining in that way. If it's not my code, I could basically rip out copyright notices and put it up there.

Rhonda Holberton 35:59

You know, maybe it's worth, you know, me try to do some homework and see if this investor is interested in, you know, opening up an academic use or, yeah,

Peter Graf 36:08

I really doubt that we can really dig up. So I could probably dig up the name of the investor. But this guy still exists. That is, that is

Rhonda Holberton 36:21

an interesting part of the history, though, I mean, you know, I think

Peter Graf 36:26

Brewster Khale, dealing with this a lot in the Internet Archive. I mean, what he does, he has this vest for, for publishing, or republishing orphan books, because with books, you very often have seen that the publisher published the book in 1960. And then the publishing house got results 17 times and nobody knows who now owns these rights to this book. And therefore you can republish it. And therefore those books, kind of even if the people who would be interested in books disappear, because they cannot be republished at all, well, of course, also disappear after a while. It also really has this quest saying, No, I'm gonna publish this stuff. And if they fight before it, it's fine. But I will not let those books die. Just this really interesting question, Should we let the software die or should be uploaded to get up? Just make sure it's that it's there forever?

Rhonda Holberton 37:20

Yeah, I mean, I think having worked a little bit with archivists, the idea is not that you're preserving it, because you know, how it's going to be used in the future, but you're preserving it, because it's an important feature, and you don't know how it will be used in the future. And I think that that that unknown, I think, is really interesting, especially when it comes to kind of deployables. You know, it's such an interesting way to think about this in software, right? The things that get archived, or that you know, are the most used are the kind of the code that's at the top of stuff, you know, Stack Exchange or something. But, yeah, what does a true you know, if GitHub starts thinking about itself as not just a repository, but truly as an archive? What features might start becoming?

Peter Graf 38:11

Yeah, but do you have the right to put something on GitHub that you don't know? So that's all the stuff that I write myself that I can put up on? There? I've written much of it, but I've written it under the name of as an employee or as an employee of Exxon. So I don't know No, right? But should I put it up on the web or on GitHub or wherever, just to make sure that it doesn't disappear? And people can look at it? And and also, somebody can history, Major,

Rhonda Holberton 38:39

new emerging fields of like digital anthropology and all, you know, if we don't do these things, right, like the code might not be used, again, as an executable or deployable, but it might exist as a framework for understanding the history. And so yeah, there's so many questions. I think it's a fascinating topic. I don't know that everybody will. But I hope that we like through these interviews, at least start conversation, right. I think it's not just us of having these questions. There's lots of institutions and other developers that are starting to think about both the legacy but also, you know, practical questions around archiving.

Peter Graf 39:12

GitHub was its Arctic world thing is clearly going on a long term although I doubt that the Arctic world as long term as they think because because what that is basically thawing. And so the Arctic Waltz is actually I read an article that the Arctic world is tilting, because it's really it was built into some rocks in Svalbard. And those rocks are the foundation of those rocks is melting and so the whole thing so they thought this would be forever and now 10 years later, the thing is testing starts to do

Rhonda Holberton 39:41

maybe one of these folks takes it to Mars with them. archive for who Right? Talk to him not socially, but yeah, we are have crosses. I love what they're doing. And one of my collaborators on this project well from Leonardo, so there's an archivist for Leonardo this work. seeing with the Internet Archive on a couple of their projects as well. So we're aware of, of one another. And I would love if I have funding or if he's interested to bring him in a little bit more deeply into the conversation, because

Peter Graf 40:12

technical is in the Bay Area, bring it up, because she can really take you to do some areas as they do a Thursday night dinner, where they invite interesting people every Thursday. And so you could really go with tonic or meek, you should come to one of the students.

Rhonda Holberton 40:27

That'd be lovely. I would love that. So I will see if I can

Peter Graf 40:32

do that really, really social people. And booster is a very old friend of mine, because they really work together. When they were both as a title like 28. And both those 22. And they work together at thinking machines, then Rostow worked on his ways project. And I've been thinking machines can the project, he turned it into a company. And it was as was the first Surgeon even before the web. And then there was a protocol basically access various search engines, which was their own protocol before HTTP see 3950 was the name of the protocol. Can you say that again? 3950. And then when the BAP happen, they realized oops, now people can basically use web browsers and HTML, or HTTP to access those things. And so it was, I worked for half a year for him. And like one of the projects I did, we brought the advertising stories, but the ads where you said like two bedroom in lower Manhattan or something. So we brought that although in the end, they didn't bring what they wanted to. So we had to there was a full text search engine basically, like there's all this code that New York Times uses the coop er, and as a two guys, that one thing I remember like two bedroom, three bath, but they had other like, because you paid for the letter. And so there was like up are then codes for for different parts of the city. So in an amount in 12 letters, you could basically say half an apartment, three bedroom, and it's in south of the third floor. And you could also break this into etc. So I wrote a search engine that basically parse those queries,

Rhonda Holberton 42:11

turn it back into like,

Peter Graf 42:15

real text, process old ways to AOL and started a company called Alexa and then sold that to something extra to Amazon. And that's where he is this morning. But then after setting an extra two hours, so he started to do such a thing, that kind of turn.

Rhonda Holberton 42:34

Yeah, turn towards philanthropy or kind of philanthropic.

Peter Graf 42:41

This is a really interesting character. I think at the age of six, he fell in love with the Library of Alexandria, didn't fall in love with Alexandria, with Alexandria, Alexandria, and everything that he has done after that was really all about the Library of Alexandria basically, getting this idea to have a physical space. In the beginning, of course, a physical space where all the knowledge of the world is together in a library and accessible for other people. This is everything he did was basically going in that direction. And now having the archive is really the archive of course.

References:

georges perec, the infra-ordinary, 1973,

https://www.ubu.com/papers/perec_infraordinary.html

alvin lucier, i am sitting in a room, 1969,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAxHlLK3Oyk

gaston bachelard, the poetics of space (the orion press inc.,

1964), 184.

kristy bell,

the artist’s house: from workplace to artwork,( berlin, sternberg

press, 2013).

wolf vostell and dick higgings,

fantastic architecture, (something else press, 1974).

Media

Video Recording of the Interview with Firstname Lastname, Conducted November 28, 2022

Module 3 Web Comparison

Title, Year

Medium

Size/Duration

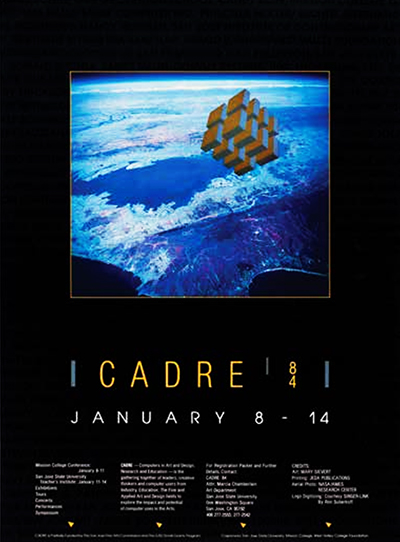

CADRE Exhibition Poster, 1984, Originally accessed 1 May 2022, https://cadre.sjsu.edu/history.

Kewords

Keyword 1, Keyword 2, Keyword 3, Keywordd 4

Disciplines

Discipline 1; Discipline 2; Discipline 3